Ideally, all consumer products that go to market have been thoroughly tested to prevent them from unexpectedly harming anyone. But occasionally something slips through the cracks; maybe the marketing team fails to include adequate instructions for the product’s use on its packaging, or a manufacturer just doesn’t realize that a small part on a child’s toy could come loose and become a choking hazard. But since product defects aren’t always obvious, how do consumers know if they have a defective product on their hands?

One of the most straightforward ways to find out if you have a defective product is to pay attention to product recalls. Unfortunately, manufacturers do not always do a very good job of broadcasting their recalls, so consumers need to take a proactive approach to discovering if they have any defective products. Concerned consumers should frequently go to Recalls.gov to search for recalled products by category or keyword.

But what if you don’t hear about a recall—or a company fails to issue a recall before you are harmed by one of their products? In that type of situation, how do you know whether you have a strong case against the company?

Proving Liability for a Defective Product

Fortunately, the people and companies who create and sell consumer goods are typically held to strict liability in defective product cases. This means that a plaintiff only has to prove that a consumer product is unreasonably dangerous in order to hold the manufacturer, designer, or marketer accountable. There are three main ways that a product may be found defective:

Product defects. Product defects affect an individual product rather than an entire line and typically occur at the manufacturing stage. For example, if a kitchen chair manufacturer failed to add several screws to one of their chairs and it collapsed when the person who purchased it sat down, that person could file a claim to recover compensation for their injuries.

Design defects. This type of defect affects an entire line of products, not just a single item. A relatively recent example of this is the defective ignition switch in certain GM vehicles that would unexpectedly turn off the vehicle’s power if a driver went over a bump or jostled their keys with their legs.

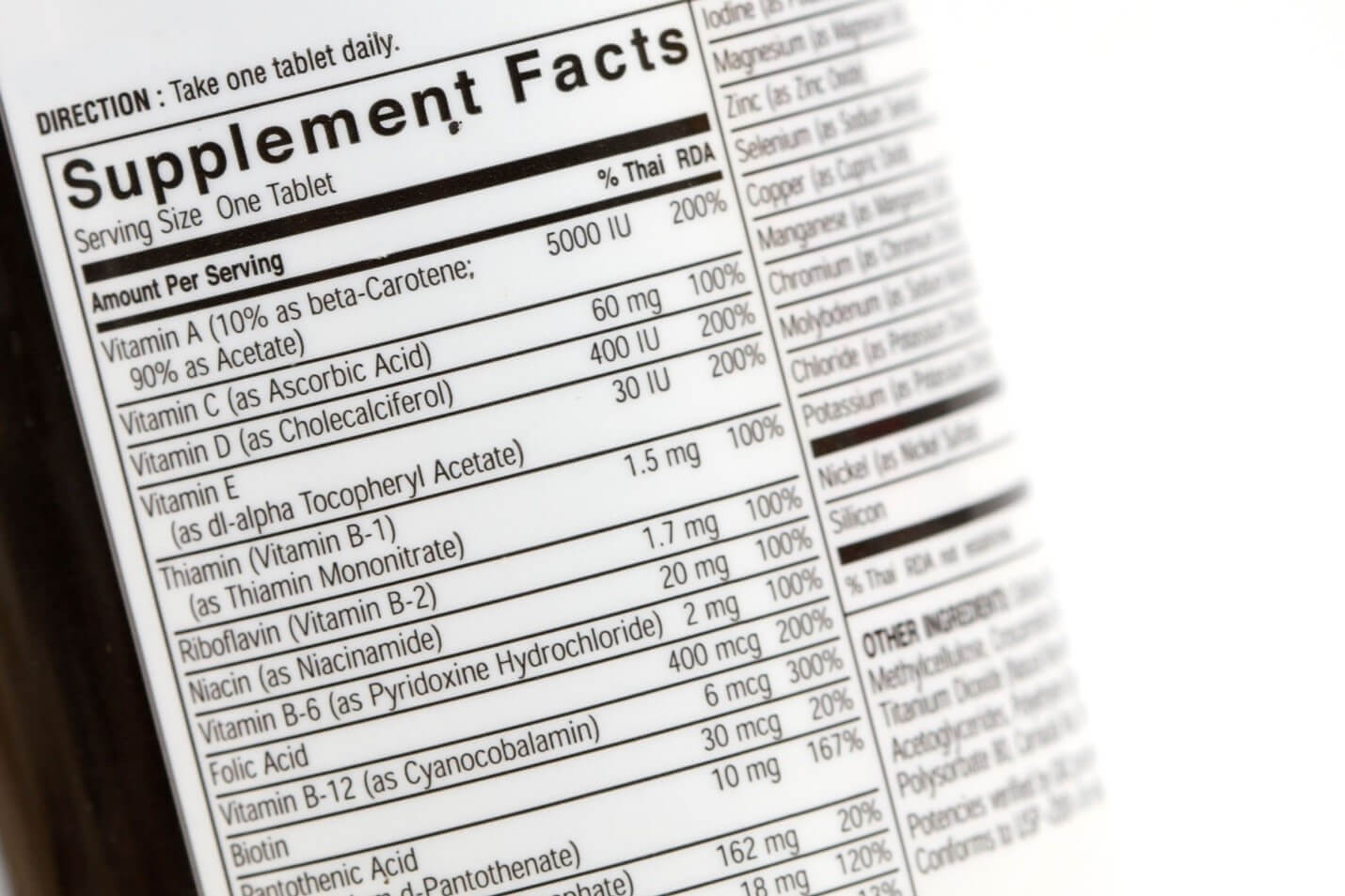

Marketing defects. There may not be a design or manufacturing issue with a product, but it can still be defective if it did not come with sufficient instructions and warnings for usage and a consumer suffered an injury as a result. For example, if a brand of sleeping pills did not come with dosage instructions, the company that produced and marketed the prescription drug could be found liable in the event of an overdose.

Res Ipsa Loquitor Cases

In some cases, a product defect is so obvious that a plaintiff would not even need to prove that the manufacturer was negligent. Under the principal of res ipsa loquitor, which is Latin for “the thing speaks for itself,” the plaintiff must simply show that the product is defective and that he or she was injured by the product, and the burden of proof shifts to the defendant. Then, the defendant must prove that they were not negligent, rather than the plaintiff having to prove that the defendant was negligent. However, plaintiffs need to be careful about using this strategy, as the defendant may try to argue that if the defect was obvious, the plaintiff must have known of the danger and used it anyway.

If you are an accident victim and are unsure whether your injury was truly caused by a defective product, or are wondering how to show the court that a product is defective, talk to an experienced personal injury attorney at the Law Offices of The South Florida Injury Law Firm.

About the Author:

Jeffrey Braxton is a trial lawyer in Fort Lauderdale who has devoted his 22-year career to the practice of personal injury law. As lead trial attorney for The South Florida Injury Law Firm, Jeff has litigated thousands of cases and is a member of the Million Dollar Advocates Forum, an exclusive group of attorneys who have resolved cases in excess of one million dollars.